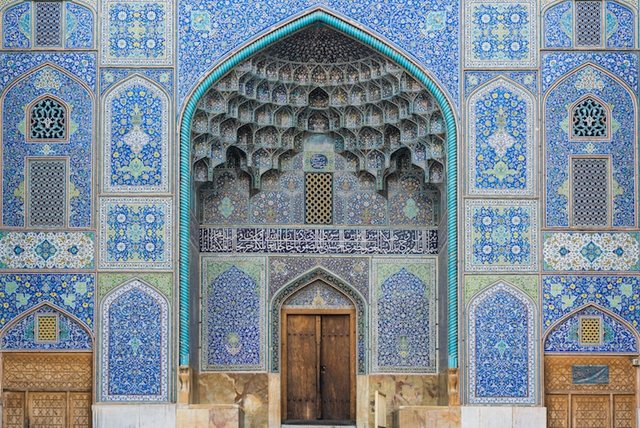

In Islamic culture, geometry is everywhere. It can be found in mosques, madrasas, palaces, and private homes. This tradition began in the 18th century CE, during the early history of Islam, when artisans borrowed motifs that had previously existed in Roman and Persian culture, further developing them into new forms of visual expression. This period of history was a golden age of Islamic culture, during which many achievements of previous civilizations were preserved and further developed, resulting in substantial advances in the study of science and mathematics.

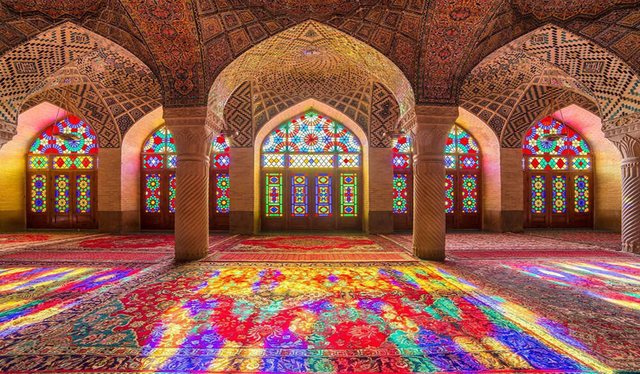

Accompanying it was an increasingly sophisticated use of abstraction and complex geometry in Islamic art, from intricate prayer motifs adorning carpets and textiles to tile patterns that seemed to repeat themselves endlessly, inspiring fascination and immersion in the order of the eternal. Despite the extraordinary complexity of these designs, they could be created simply with a compass to draw the circles, and a ruler to draw lines within them. And from these simple tools flowed a kaleidoscopic multiplication of patterns.

But how does something like this work in practice?

It all starts with a circle. The first major decision is how you're going to divide it. Most designs divide the circle into four, five, or six equal sections. And each division gives rise to other distinctive patterns. There's an easy way to determine whether any design is based on a quadrilateral, pentagonal, or hexagonal symmetry. Most feature stars surrounded by petal shapes.

Counting the number of rays from the center of the light source, or the number of petals around it, tells us which category it belongs to. A star with six rays, or surrounded by six petals, belongs to the hexagonal category. While one with eight petals, is part of the tetrahedral category, and so on.

There's another secret ingredient in these designs: a coordinate grid that hides beneath the main design. Invisible but essential to any model, this coordinate grid helps determine the scale of the composition before work begins, ensures that the model remains accurate, and makes it easy to invent incredible new designs.

Let's look at an example of how these elements all come together. We'll start with a circle inside a square and divide it into eight equal parts. Next, we can draw a pair of lines that intersect, overlapping each other. These lines are called construction lines, and by selecting a set of their segments, we can form the basis of our repeating patterns. Many different designs are possible from the same construction lines, simply by selecting different segments.

And the complete pattern, finally, emerges when we create a grid of coordinates with many iterations of this single tile in a process called tessellation. By choosing a different set of construction lines, we could have created this pattern, or that other one. The possibilities here are visually endless.

We can follow the same steps to create hexagonal patterns, by drawing construction lines on a circle divided into six parts, and then placing it in a mosaic, and then we will have something like this. Here we have another hexagonal pattern that has appeared over the centuries and throughout the Islamic world, including Marrakesh, Agra, Konya, and the Alhambra. The quadrilateral patterns fit into a coordinate grid, and a hexagonal pattern into a hexagonal grid. The quadrilateral patterns fit into a square grid and the hexagonal patterns into a hexagonal grid.

However, pentagonal patterns are the most challenging to mosaic because pentagons do not completely fill a surface, so instead of creating a pattern on a pentagon, other shapes must be added to make something that can be repeated, resulting in patterns that may appear indistinguishable from complex, but are still relatively simple to create.

Also, mosaic is not limited to simple geometric shapes, as the work of MC Escher shows. And while the Islamic tradition of geometric designs does not tend to employ elements such as fish and faces, it sometimes uses multiple shapes to work into complex patterns.

This more than 1,000-year-old tradition has used basic geometry to produce intricate, decorative, and visually pleasing works. And these masters have proven how much is possible with a little artistic intuition, creativity, dedication, and a large compass and ruler.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pg1NpMmPv48